The Perfect Idea

The reality behind reality

“Aristotle taught that there was an immovable ‘entelechy’ in the universe that moves everything and that thought was its main attribute. I am also convinced that the whole universe is unified in both material and spiritual sense. Out there in the universe there is a nucleus that gives us all the power, all the inspiration; it draws us to itself eternally, I feel its mightiness and values it transmits throughout the universe; thus keeping it in harmony. I have not breached the secret of that core, still I am aware of its existence, and when wanting to give it any material attribute I imagine light, and when trying to conceive it spiritually I imagine beauty and compassion. The one who carries that belief inside feels strong, finds joy in his work, for he experiences himself as a single tone in the universal harmony.” ~ Nikola Tesla

Divine Ideations

Philosophical inquiry into the nature of ideas has been a central preoccupation of Western thought since antiquity. The concept of “idea” emerged within the context of Greek philosophy and has been further developed and refined by subsequent philosophers in the Western tradition.

Western philosophies traditionally place a dominant emphasis on reason, logic, and analysis as a means of comprehending the world, while Eastern philosophies tended to value intuition, direct experience, and contemplation as ways of accessing deeper truth about the nature of reality.

The question “what is an idea?” has been approached from diverse perspectives, each offering distinct epistemological and ontological claims. Herein we examine the nature of ideas, from some Western philosophical perspectives.

The general definition of “idea” is a “rough mental impression … a thought, suggestion, opinion, belief or intention.”

In saying something like “I have an idea, I think I'll write an article,” that would fit a general definition. But in the context of this discussion, such is more an impulse, perhaps driven by an inspiration of what the article will be about. The inspiration gives rise to the idea to be written of. This greater definition of Idea is what we are seeking.

Plato taught of an ideal realm of forms or archetypes as the source of true ideas. He posited that ideas are real entities that exist in a transcendent realm beyond the physical world; the “world of Forms” or the “realm of ideas.”

To Plato, ideas are eternal, the true reality. They are perfect concepts existing independently of our physical world, which is but a shadow or reflection of the perfect world of ideas. Physical objects are imperfect copies of these ideal Forms. Ideas are perfect and unchanging, and can be apprehended through reason and intuition. The ultimate aim of Plato’s philosophy, therefore, is to attain knowledge of the ideal Forms, utilizing this knowledge to live a just and virtuous life.

In Plato’s allegory of the cave, in The Republic, Socrates describes prisoners in the cave as living in a world of shadows and illusions, mistaking the shadows on the wall for reality. He explains that objects in the physical world are merely imperfect copies of the eternal and unchanging Forms that exist in the Ideal realm.

In Platonism, the soul is divided into three parts: the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive.

The rational part of the soul is considered to be the most important and is associated with the pursuit of knowledge and understanding of the ideal realm of Forms. This part is responsible for reason, logic, and contemplation, and it is through its proper functioning that the individual can attain the highest level of comprehension and insight.

The spirited part brings forth courage, honor, and ambition, and it is through its proper functioning that the individual pursues his or her goals and aspirations.

The appetitive part controls desire, pleasure, and instinctual drives, and it is through its proper functioning that the individual can satisfy his or her basic needs and impulses.

To Plato the goal of human life is to cultivate the rational part of the soul, to bring it into harmony and integration with the spirited and appetitive parts. By doing so, individuals can become closer to the perfect realm of ideas, thereby achieving true knowledge and the attainment of wisdom, enlightenment, and spiritual fulfillment.

Plato considered the so-called “Platonic solids” to be ideal forms because they are perfectly defined geometric polygons, thereby with a timeless existence in the realm of Forms.

Plato believed that each of the four ancient elements was associated with a specific equal-sided polygon:

cube for earth,

icosahedron for water,

octahedron for air,

tetrahedron for fire.

These shapes are the most perfect and stable arrangements of the “atoms” that make up each of the ancient elements.

The dodecahedron was considered to be the shape of the universe, with its twelve faces representing the twelve signs of the zodiac, and the aether that fills the cosmos. Plato saw the universe as a harmonious, geometrically perfect creation, and the Platonic solids are an expression of that perfection.

Born With a Blank Slate

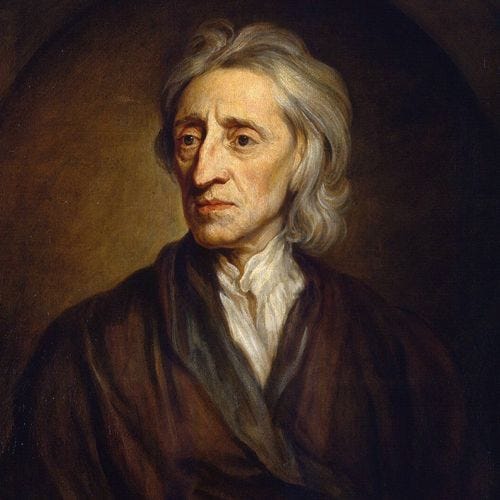

Philosophers who did not teach that we are inherently able to attain direct knowledge of the ideal realm of forms or archetypes include Aristotle, John Locke, and Immanuel Kant.

Aristotle had a more empirical view of ideas. Aristotle believed that ideas are derived from sensory experience and are not separate entities existing beyond the physical world. According to Aristotle, ideas are concepts or mental representations that are formed by abstraction from particular instances, from the objects & events we experience in the physical world.

Aristotle taught that ideas have a grounding in the material world and that they are not just copies of sensory experiences, but rather general concepts that have a basis in the material world. Concepts are not ‘real’ in the way that physical objects are real, but they have a real existence in the mind and are based on the patterns and regularities that we observe in the physical world.

Thus we see a distinct difference between Plato’s and Aristotle’s concepts of what an idea is. To Plato, a true idea originates in and is inspired from the Divine, with an archetypal nature we can connect to through development. To Aristotle, ideas arise purely from our experiential interactions with the world.

Philosopher and physician John Locke had a similar view of ideas to Aristotle. Locke believed that all ideas are derived from sensory experience and that the mind is a blank slate at birth, without any innate ideas or concepts. He thought that even complex ideas were ultimately built up from simple ideas derived from sensory experience. Locke’s emphasis on sensory experience and empirical observation laid the groundwork for the so-called “scientific method,” which has become the dominant mode of inquiry in the modern era.

Locke’s concept of the idea played a crucial role in his distinction between Primary and Secondary Qualities.

According to Locke, Primary Qualities are the objective, inherent properties of objects that exist independent of our perception of them. These include properties such as weight, shape, size, position and motion.

Secondary Qualities, on the other hand, are the subjective properties of objects that are dependent on our perception of them, such as color, taste, sound, touch and smell… you know, the input of our senses!

Locke’s concept of the idea was fundamental to his argument that Secondary Qualities are not inherent in objects themselves, but rather arise from our subjective perception of them. He argued that we can only know about the properties of objects through our sensory experience of them, and that these sensory experiences give rise to ideas in our minds. For example, the sensation of redness gives rise to the idea of red in our minds. But it is not actually red in this thesis, that is purely subjective, caused by activities of the Primary Qualities.

Locke claimed that our ideas of Secondary Qualities do not resemble the qualities themselves. Rather, they are merely the result of the way our minds are affected by external objects. This led him to the conclusion that our ideas of Secondary Qualities are not accurate representations of the qualities themselves, but rather are subjective constructions that arise from our interactions with the world. Primary Qualities are objective properties of objects that exist independently of our perception of them.

Immanuel Kant also rejected the notion of our attainment of direct knowledge of a non-physical realm of ideas, but he believed that the mind actively structures our experience of the world through categories and concepts that are innate to human reason.

Immanuel Kant’s view of ideas represented a significant departure from previous philosophical positions. Kant believed that there is a supersensible realm, the noumenal, that exists beyond our experience, one we can never access directly in our human state of waking consciousness.

According to Kant, this noumenal realm includes things like God, free will, and the soul, which are beyond the reach of our senses and our comprehension. Kant thought that our minds have innate structures, which he called categories, that allow us to organize our experience of the world and build knowledge. These categories are not derived from experience but are instead innate to human reason.

According to Kant, humans can only know objects through the way they appear to us, not as they are in themselves. Kant called this the “thing-in-itself,” the unknowable essence of objects that exist independently of human perception and understanding. The thing-in-itself is forever beyond human understanding and cannot be known or experienced directly, but only through its effects on our senses and our ability to reason about those effects.

He said our minds are intellectus ectypus, reaching cognition by way of ‘images’ of something in the world of external reality, as distinguished from its eternal and ideal archetype. This intellectus ectypus is restricted to taking in through the senses single ‘image’ details of the world. With these images humans can certainly construct pictures of objective totalities, but these pictures never have more than a hypothetical character and can claim no reality for themselves.

This is an important concept in Kant’s philosophy because it suggests that human knowledge is inherently limited by the structures of our minds, and that we can never gain full knowledge of the world as it truly exists.

This characterization of the human intellect raises the possibility of another form of intellect, the intellectus archetypus, or cognition directly through the original. In such a case, there would be no distinction between perceiving a thing, understanding a thing, and the thing existing. This would be, to Kant, as close as our finite human minds could get to knowing the “Mind of God,” but we are forever restricted by our intellectus ectypus.

Kantian philosophy is overall based on a limited comprehension of human consciousness, placing too much emphasis on abstraction and reason, and not enough on observation and experience. His distinction between the phenomenal (objective) and noumenal (subjective) worlds is a form of dualism at odds with a wholistic and integrated approach.

Kant’s philosophy is thereby one of placing limits on cognition, and is the foundation of the materialist scientific paradigm.

Perfect Ideas

The German poet-scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had a unique view of ideas that was deeply informed by his engagement with natural phenomena. Goethe considered that perfect ideas are those which are grounded in the natural world, capturing the unity and interconnectedness of all things. He saw that the natural world is full of archetypal forms, being the essential qualities of objects, and that these forms could be cognized through a process of exact sensorial imagination.

Goethe maintained, thusly, that he had achieved in practice what Kant declared to be forever beyond the scope of the human mind.

Traditional scientific methods, reliant on abstraction and analysis, are inadequate for comprehending the complexity and interconnectedness of natural phenomena. They are too focused on breaking down natural phenomenon into smaller and smaller parts, and not enough on comprehending the whole. This reductionist approach leads to a fragmented and incomplete comprehension of nature. A more wholistic and intuitive approach is necessary to gain direct knowledge from Nature, which Goethe terms Intuitive Judgment.

Goethe’s way of knowing combines observation, imagination, and experience, allowing direct cognizance of the overarching principles of natural phenomena. His participatory method of observation allows for a higher clarity of perception of Nature through recognizing the interconnectedness and interdependence of all things.

The Goethean approach provides a functional pathway to higher knowledge of the spiritual realms manifesting in and through Nature, what we can experience as an expression of the “Mind of God,” that which Kantian philosophy forbids as impossible.

This, of course, engenders thoughts of intelligent design in Nature, which implies an inherent archetypal realm. Can we truly gain direct awareness and knowledge of this intelligence with Intuitive Judgment?

Goethe’s secret was that he was in the grip of the process of archetypal transformation which has gone on through the centuries. ~ Carl Jung

Rudolf Steiner’s philosophy holds that the realm of Ideas or Forms is the spiritual realm, permeating and interpenetrating the physical world. Ideas are not mere mental constructs or abstractions, they are living spiritual beings continuously evolving and developing along with us.

These spiritual beings comprise the members of the spiritual realm, the source of all life and creativity, which may be perceived by human consciousness through intuition and inner perception. They are transformed and enriched by human creative activity and can be made manifest in the physical world through artistic and cultural expression.

The spiritual realm is not abstract or theoretical, rather it is an absolute reality that can be directly experienced through spiritual practices and disciplines. Human beings are essentially spiritual beings, inherently capable of developing a deeper comprehension of the spiritual world and the nature of reality.

Through spiritual practices such as meditation, inner reflection, and artistic expression, as well as the Goethean approach to natural science, human beings can come to perceive and participate in the realm of ideas, contributing to their evolution and development.

In Steiner's view, the spiritual realm is structured into a hierarchy of beings, with the highest beings being the Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones. As one's capacity for intuitive ideation becomes more refined and spiritual, one can cognize higher up into the hierarchies. This hierarchy ranges from the highest to the lowest, with Archangels and Archai being among the higher beings, and Nature spirits and elemental beings being among the lower ones. The spiritual beings associated with the highest levels of the spiritual realm are responsible for humanity's highest spiritual ideals and aspirations.

Each of these beings is responsible for a particular aspect of the world and its evolution, and is associated with a particular level of spiritual reality. The spiritual ideas that human beings can perceive and understand are seen as emanations or reflections of the spiritual beings and their activities in this world.

Through cultivation of one’s inner spiritual senses while developing a deeper comprehension of the spiritual realm and its hierarchies, human beings are able to participate in the spiritual evolution of the cosmos. This process of spiritual evolution involves the gradual refinement and transformation of human consciousness as the individual ascends through the hierarchies, coming into closer alignment with the highest spiritual ideals and principles. This process involves the cultivation of spiritual virtues such as love, wisdom, and compassion, and the development of a deepening awareness of the spiritual realities that underlie the physical world.

While some may follow a devotional, meditative pathway to these higher realms, they can also be approached in a more functional manner through the Goethean participatory scientific approach. This approach involves observation and participation in the natural world to gain a deeper understanding of its workings and to participate in its evolution.

Myself, I have not directly experienced the hierarchies distinctly as propounded by Steiner and other similar schools, yet my experiences have provided visions of the archetypal realm through cognizing natural processes. So I do comprehend the logic, and can see where an advanced soul is able to have more direct knowledge.

The reasoning for this sojourn, ruminating on ideations of the subsensible and supersensible is to begin to see how technologies can be inspired by Nature herself, by the formative archetypes of living forms and processes. We can thereby play a role in engendering a paradigmatic metamorphosis beyond the discursive sciences of today. To do so we must explore the processes of gaining archetypal cognition, otherwise there will be no true foundation for exploring utility.

So let’s investigate how one may develop their exact sensorial imagination via peering into the natural world, following Goethe’s participatory approach.

Next…

Thanx again Thomas! So, the highest entities of spiritual hierarchies powers on earth, transmitted and received are less obstructed when the collective human thoughts birthed into to the Eather, align with the divine prime objective of evolution. That It may behoove one to accept some responsibility for the response ability of the higher spiritual benevolents by participating in the currency of symbiotic virtuous thought. IMHO, I personally believe the conduits of communication to be entities of light. "All knowledge comes from the stars. Men do not invent or create ideas; the ideas exist and men are able to grasp them." - Paracelsus