Seeing the Whole of the Plant

Actualizing the Archetypal Approach

“Nature is, after all, the only book that offers important content on every page.”

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

When we look at a plant, what do we see? Only its physical form at some particular stage of its growth cycle.

We cannot see the whole of a plant with our physical eyes, in our discursive state of consciousness.

How may we perceive more than what appears simply before us in physical form?

And how do we actually recognize any one of the manifold species as plants upon simple observation?

What defines a plant?

Technically, a plants are multicellular eukaryotic organisms belonging to the kingdom Plantae, characterized by their ability to produce their sustenance through photosynthesis, utilizing sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water in creating glucose and oxygen.

Plants exist in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, from tiny mosses to towering trees, of extremely diverse types, integral as part of functioning of Earth’s ecosystem, producing oxygen, removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and providing food and habitat for many other organisms.

Humans, along with our “evolutionary” relations in the faunal kingdom, are symbiotic with plants, we cannot live without breathing in the oxygen they supply. In reciprocity, plants require our carbon dioxide exhalations. This symbiosis goes much deeper, for now this is sufficient to make the point.

The floral kingdom comprises approximately 80-90% of the biomass of the biosphere, the 10-20% being faunal, a small percentage microbiome.

Plants are cause and effect within themselves, an Ouroborian-type process constituting the entire vegetative surface of our planet, each individual interrelated to that wholeness.

Following the Goethean approach to deep comprehension of the natural world, we may engender seeing the whole of a plant as a living, dynamic organism beyond our immediate discursive observations. By doing so, we gain knowledge of the fundamental interrelationship of all living beings, opening ourselves to cognizing spiritual aspects of the natural world in a functional manner.

A prolegomena to a pragmatic metaphysics.

Modern science, in thralldom to the reductive, discursive approach, chops plants up into parts, studies the pieces under microscopes and through chemical assaults, and attempts to grasp the wholeness of the living plant in this this doomed-to-failure manner.

When humans are born, without structural defect, we can say: that is the whole of the human, an ensouled being from birth to death, all the same organs throughout, with their changes through teeth growth in youngsters, puberty and menopause transformations acknowledged, as long as accident and doctors haven’t altered anything.

According to many esoteric traditions, our organs are ensoulments of the planets, the macrocosm within as the microcosm.

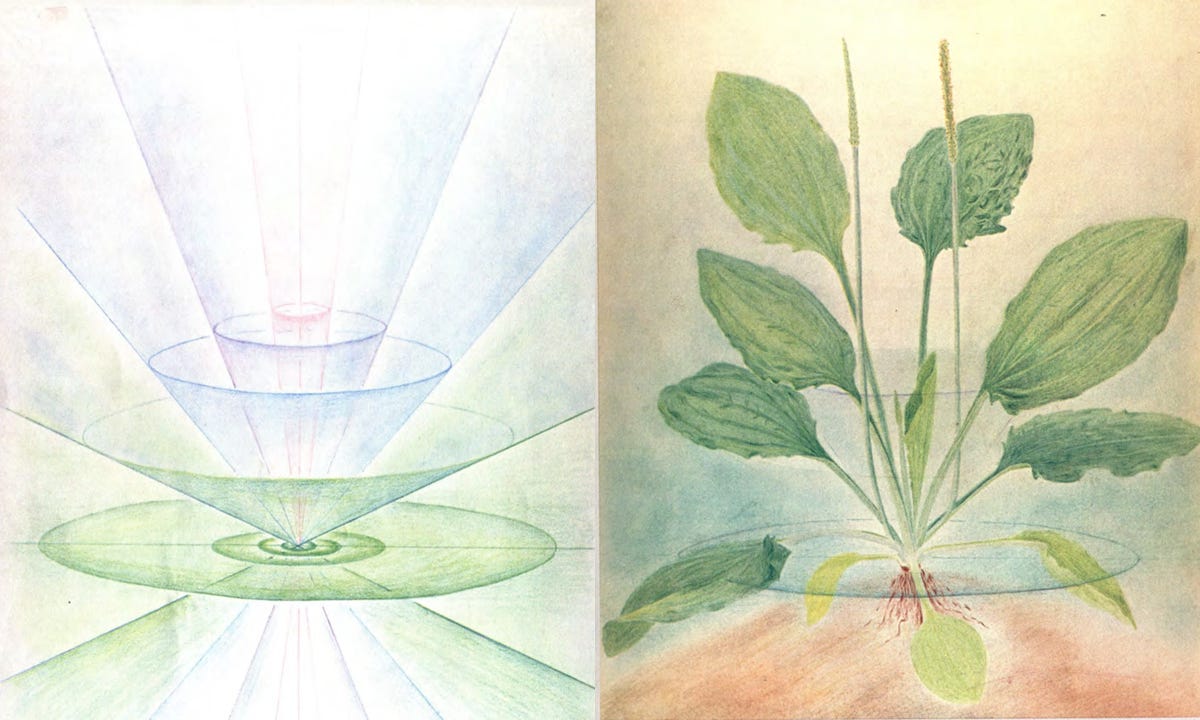

About a plant, we cannot say similar. A seed isn’t like a sponge that expands when wet, its stem, leaves and flowers hidden inside waiting to spring into sight. More mysterious processes entail as it grows into space — some say woven by the light ether — with its levity force drawing it upwards contra-gravity. That which exists between seed to seed, this constitutes the whole physicality of a plant organism.

To fully comprehend the essential nature of a plant, one must participate in the cognitive process of building the flowing imagery of the entire plant cycle, from seed to shoot, stem, leaves, flower, fruit, and back to seed, in their imagination. Plants have only one organ, the plant itself, which metamorphoses through these stages.

By seeing the beauty and wisdom in each phase of growth, to deepen our comprehension of the natural world and our place in it, we employ the Goethean process. We utilize our eye of the spirit to meditate on a plant as it grows through its stages of growth and metamorphosis. This process involves building these stages in our consciousness, in both space and time. Through this process we gain a deeper comprehension of the whole plant and its archetypal nature. We must become one in consciousness with the plant to experience its true nature.

In the past, one had to invest weeks, months, years to take in the wholeness of a species’ growth cycle. Now, we can watch time-lapse videos of plant growth to accelerate this level of consciousness in our minds with diverse plant species. From there it naturally requires further study, meditation and imagination to cognize the flow. One must begin somewhere, and today is a great day.

The whole of a plant is a complex organism comprised of physical, etheric, and astral elements, interacting to produce the various aspects of the plant’s form and function. To comprehend the whole of a plant, we need to combine scientific observation with spiritual insight. A comprehensive wholistic approach is requisite, as a reductionist, mechanistic approach cannot capture the essence of a plant as a living, dynamic organism.

In observing a plant carefully and intuitively, we begin to comprehend its individuality and consciousness. We also begin to experience the plant in the context of its environment and surrounding ecosystem, as it is part of a larger web of interrelationships and interdependencies.

Goethe’s participatory method of comprehending the natural world places our minds on par with Nature herself. This approach involves actively participating in the phenomenon being studied and allowing the outer world to call forth our inner world. By engaging with Nature in this way, we come to see the world not just phenomenally, but also archetypally.

For Goethe, color and light from the Sun call forth sight. The living phenomenon shares roots with the roots of our mind. To truly comprehend phenomenon in Nature, we have to participate in that which brings it forth. By meeting and participating in each other, we come to a deeper comprehension of the natural world and our place within it.

Urpflanze

“The archetypal plant shall be the most marvelous creature in the world, and nature shall envy me for it. With this model and the key to it one can invent plants ad infinitum that must be consistent, i.e. that could exist even if they do not in fact, are not just picturesque shadows, but have instead an inner truth and necessity.” — Goethe

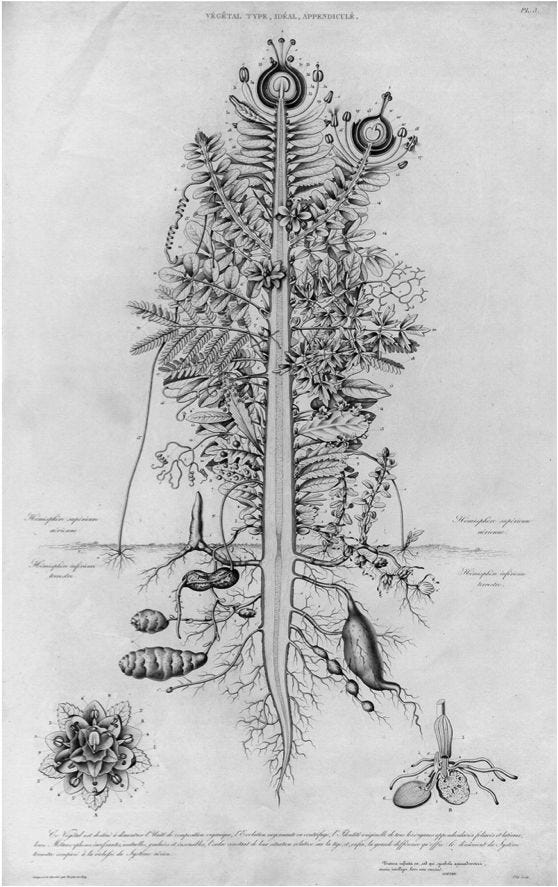

Goethe's urpflanze or archetypal plant is a ideal plant that he envisioned as contained the basic blueprint or pattern for all plants. Every plant is a manifestation of this archetype, each in its unique form, or “type.”

His urpflanze challenged the prevailing view of plant classification at the time, which relied heavily on a reductionist approach based on the physical characteristics of plants. In contrast, Goethe’s approach emphasizes the interrelated oneness of all living beings, what we may conceive of ultimately as the living biosphere, each plant and animal integral to the whole.

Goethe’s concept of the urpflanze has had a profound influence on plant morphology and our knowledge of the natural world. The urpflanze is the ideal form of all plants that exist in the mind of the Creator.

This idea is similar to Plato's theory of forms, in which the physical world is a shadow or reflection of a perfect realm of ideal forms. However, unlike Plato’s perfect forms, one of the most significant contributions of Goethe’s concept of the urpflanze is the recognition that plant morphology is not fixed or predetermined, but is constantly evolving and adapting in response to environmental factors. Goethe argued that plant growth and form are the result of a dynamic interplay between a plant’s inner nature and external conditions. This inner nature is the individual type’s expression of the archetype.

“Our spirit must . . work much more intensely in comprehending the type than it does in discovering the laws of nature. It must take up a function that in the inorganic natural sciences is done by the senses, and which we call intuition. On this higher level, the spirit itself must be intuitive. Our judgment must perceive thoughtfully and think intuitively.” — Rudolf Steiner

Metamorphosis

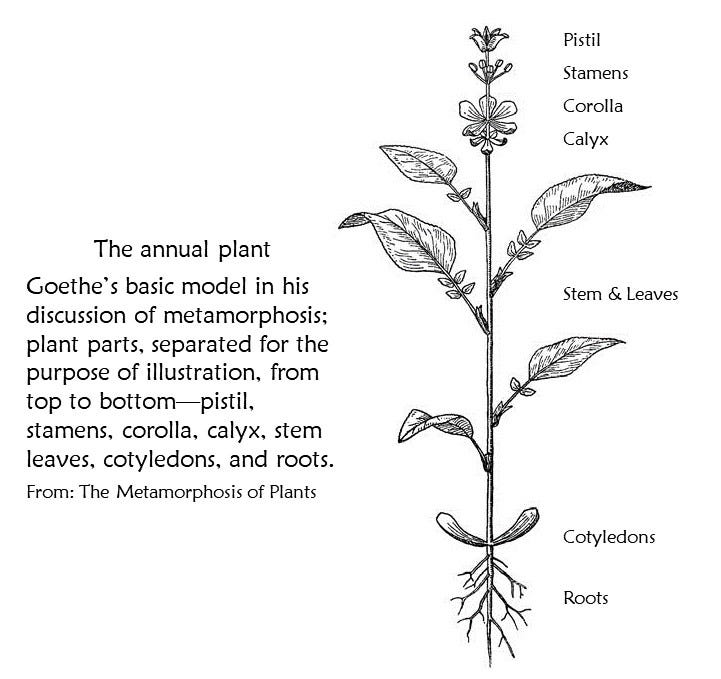

According to Goethe's theory of metamorphosis, each plant type, as aspect of the urpflanze undertakes a series of developmental stages or metamorphoses, each of which represents a different aspect plant life.

Goethe’s theory highlights the transformation of plant structures through their growth and development cycles. In this process, each part of the plant undergoes a transformation and takes on new roles, culminating in the formation of the next generation of seeds.

Each stage represents a different aspect of the plant’s development, its progress is influenced by environmental factors such as light, temperature, and humidity. But the environmental factors are are only influences upon the expression of the inner nature of the type metamorphosing through its stages.

Expansion and Contraction

Goethe saw in the life of higher plants a threefold rhythm of expansion and contraction, with each stage being crucial to the plant’s life cycle.

The first stage involves expansion from the seed into the leaf and leaf-bearing shoot, followed by the contraction into the calyx. During this stage, the plant experiences a surge in its life force, thanks to photosynthesis via the absorption of sunlight. This process stimulates cell elongation and promotes the development of new tissues. As the plant matures, it focuses its resources on strengthening existing structures and developing a robust root system, which will enable it to support its growth and withstand environmental stresses. The contraction phase involves the plant redirecting its energy towards the development of its reproductive structures, such as the calyx, which surrounds the flower bud, protecting it as it grows and matures. The calyx is formed through the contraction of the plant’s energy, allowing it to redirect resources towards the development of its reproductive structures. This contraction sets the stage for the second stage of expansion and contraction, where the plant will produce flowers and initiate the growth of fruits.

The second stage of expansion and contraction is crucial in the life of the plant. It occurs during the growth of flowers, where the plant undergoes a series of complex physiological changes. During this stage, the plant redirects its resources towards the development of its reproductive structures, culminating in the production of flowers. The plant experiences an expansion into the colored petals, which are designed to attract pollinators such as bees and butterflies. As the petals reach their full size, the plant then undergoes a contraction into the pistil and stamens. The pistil is the ‘female’ reproductive organ of the flower, while the stamens are the ‘male’ reproductive organs. The contraction aspect of this stage represents the integration of the plant’s reproductive energy, where it gathers its resources and focuses its energy on the growth and development of its fruits. The plant relies on this contraction to prepare for the final stage of expansion and contraction, where the fertilized ovary will develop into a mature fruit.

The third stage of expansion and contraction occurs during the growth of fruits, where the plant undergoes the expansion of the fertilized ovary into the fruit, followed by the supreme contraction into the seed. While seed production is the dominant contraction aspect of this stage, perennials also prepare for future growth by storing nutrients and energy. Nutrient storage occurs primarily in the plant's roots, stems, and leaves, which are redistributed to support future growth. Although seed formation is the most significant manner plants utilize to store nutrients for future growth, it is not the only way.

Straight and Spiral

Goethe’s theory of the straight and spiral tendencies in plant growth highlights the interplay between the upward and lateral growth of plants. The straight tendency provides the overall structure and direction, while the spiral tendency provides the detail and variety. For instance, the straight growth of the stem provides the plant with a stable foundation and structure, while the spiral growth of the leaves and branches provides the plant with the flexibility and adaptability to respond to changes in its environment. The complementary growth processes of straight and spiral work together to create a balanced structure that allows the plant to adapt to changing conditions.

An integrative and multidisciplinary approach is required to study the intricate processes of Nature, which exists as a complex living beingness in space and time. The concept of the urpflanze provides a wholistic perspective on plant growth and development that acknowledges the interrelationships of all aspects of the natural world.

Each plant species undergoes its ‘personal’ type stages, of metamorphosis, expansion and contraction phases, and straight and spiral growth tendencies. Comprehending the spiritual significance of these processes deepens our cognitive awareness of the natural world and our relationship to it. The concept of the urpflanze reminds us that plants are not just mechanical objects to be studied or exploited, rather they are living beings with unique qualities and contributions to the web of life. Through conscious awareness of this all we may gain a more sustainable and harmonious relationship with the natural world, and thusly begin to gain real knowledge of the higher worlds from which this living one emanates.

Influences and connections

Goethe’s botanical ideas had a profound influence on Rudolf Steiner. Steiner taught that plants are conscious beings with their own unique individualities, and that they can be comprehended and nurtured through spiritual insights and intuition.

Steiner expanded on Goethe’s concepts seeing the plant as a spiritual entity with a relationship with the cosmos and the spiritual world. He taught that plants have a unique role in the evolution of consciousness, and developed his system of BioDynamic agriculture that aimed to harmonize the spiritual and physical aspects of plant growth. The BioDynamic approach includes working with the cycles of the moon and the planets, as well as the application of spiritually inspired BioDynamic “preparations” which enhance the life forces in the plant and soil.

Steiner emphasized the importance of knowing the whole of a plant and its relationship to the environment, including the role of other flora and fauna. He recognized the interdependence of all living beings in the biosphere, and taught the necessity for a wholistic approach to agriculture and land management.

Astral and Etheric

The etheric body is the life force animating all living things. The etheric body is a non-physical, spiritual energy field that surrounds and permeates the physical body of living beings. It is responsible for the basic physiological functions of a plant, such as growth, development, and reproduction. It is also responsible for the plant’s ability to perceive physical stimuli, such as light, gravity, and touch. The etheric body is sometimes referred to as the “vital body” of the plant because it animates and enlivens the physical body.

“Now whether it be man or any other living being, the living being must always be permeated by an ethereal—for the ethereal is the true bearer of life, as we have often emphasized. This, therefore, which represents the carbonaceous framework of a living entity, must in its turn be permeated by an ethereal. The latter will either stay still —holding fast to the beams of the framework—or it will also be involved in more or less fluctuating movement. In either case, the ethereal must be spread out, wherever the framework is. Once more, there must be something ethereal wherever the framework is. Now this ethereal, if it remained alone, could certainly not exist as such within our physical and earthly world. It would, so to speak, always slide through into the empty void. It could not hold what it must take hold of in the physical, earthly world, if it had not a physical carrier. This, after all, is the peculiarity of all that we have on Earth: the Spiritual here must always have physical carriers. Then the materialists come, and take only the physical carrier into account, forgetting the Spiritual which it carries.” — Rudolf Steiner, Agriculture Course, Lecture Three

“Now the plant has in it no real astral body.” — Rudolf Steiner

Steiner taught that the astrality around the plant is more diffuse and not concentrated in a single body like it is in animals and humans. The astral forces work through the plant’s physical and etheric bodies. This vital force is responsible for the plant’s growth, development, and reproduction and is connected to the wider cosmic forces that influence the plant’s growth.

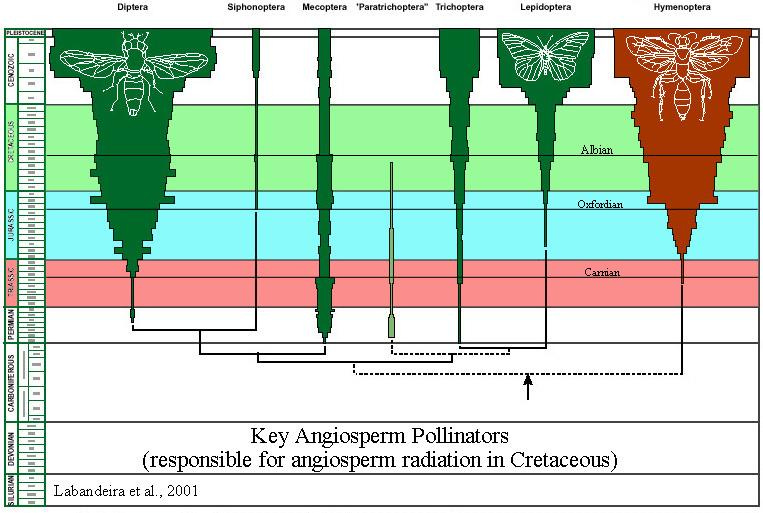

According to Steiner, insects play an essential role in the relationship between the plant’s astral influences and the surrounding atmosphere. Insects, particularly those that pollinate plants, are able to sense and respond to the astral qualities in plants, creating an atmosphere that was in resonance with the plant’s astral qualities.

Insects are able to facilitate the transfer of astral forces between the plant and the atmosphere, which is essential for the health and vitality of both the plant and the insect.

Steiner's view of a plant’s astrality is complex and multifaceted, seeing it as an essential aspect of the plant’s vitality and connection to the wider cosmos.

Interactions in the Biosphere

From a Goethean approach, plants are essential components of the biosphere due to their interactions with other organisms, floral, faunal and the microbiome. The microbiome, plays a critical role in nutrient cycling and disease prevention. Microbes in the soil break down organic matter and release nutrients that plants can absorb. They also produce antimicrobial compounds that protect the plant from harmful pathogens. In turn, the plant provides the microbes with a source of carbon, through its roots, in the form of carbohydrates, such as sugars and starches, which are produced during photosynthesis.

An important component of the microbiome are mycelium networks, vast underground fungal networks that connect multiple individuals within and across different plant species. These networks transfer nutrients and resources between plants, allowing them to thrive in nutrient-poor environments. Mycelium networks are an integral component of the microbiome, crucial for the survival of many species, ensuring the transfer of energy and nutrients throughout the ecosystem.

In addition to interacting with the microbiome and mycelium networks, plants provide food for herbivores, which in turn become food for carnivores. Plants also form symbiotic relationships with certain species of insects that act as pollinators, further ensuring the survival of plant species. The interdependence between plants and other organisms is vital for maintaining the health and balance of the biosphere.

Seeing the whole of a plant goes far beyond our immediate discursive observations, and emphasizes the plant as a living, dynamic organism with its own individuality, consciousness, and spiritual significance. Through the Goethean approach we deepen our awareness of the interconnectedness of all living beings and the spiritual sources of the natural world. Comprehending the interactions between plants and other organisms in the biosphere, such as mycelium networks, the microbiome, and the diverse flora and fauna, is essential for developing sustainable agricultural and conservation practices.

Tropisms & Nastic Movements

Tropisms are different growth movements of plants in response to external stimuli. These movements affect the rate and direction of plant growth and impact the overall morphology and physiology of a plant from environmental factors.

Some flowers, such as sunflowers - Helianthus annuus, follow our Sun during the day, a phenomenon known as heliotropism. Heliotropism is a plant’s growth or movement in response to a directional stimulus such as light, gravity, or touch. In the case of sunflowers, they exhibit a type of heliotropism called “solar tracking,” where they follow our Sun’s sojourn from East to West during the day to maximize their exposure to sunlight. At night, the flowers turn back towards the east in preparation for the next day's sunlight. Curiously, a study conducted in 2016 (DOI: 10.1126/science.aaf9793) found that sunflowers that were grown in a windowless room still displayed these heliotropic movements, even though they were not exposed to any external light source. Perhaps there is more to “sunlight” than just the visible spectrum!

Phototropism is movement of a plant towards or away from light (natural or artificial), evident in the bending of plant stems or leaves towards a light source, which is a result of the unequal distribution of plant hormones. Gravitropism is movement towards or away from gravity. Roots grow towards the ground in response to gravity, while stems and leaves grow upwards. Hydrotropism is movement towards or away from water, as in the growth of roots towards a water source. Thermotropism is movement towards or away from changes in temperature. Chemotropism is movement towards or away from certain chemical substances, such as soil nutrients. Thigmotropism is movement towards or away from touch or physical contact. Anemotropism is movement of a plant towards or away from wind. Chronotropism is growth or movement of a plant in response to changes in the duration of light and dark period. Electrotropism is growth or movement in response to electric fields.

Tropisms are a form of adaptive response by plants to their environment, allowing them to optimize their growth and survival. While they may not have the same type of intelligence as animals, plants exhibit sophisticated apparent intelligence in sensing and responding to their surroundings, and tropisms are an important part of this.

Nastic movements are non-directional, reflexive plant movements in response to environmental stimuli. Unlike tropisms, nastic movements do not involve directional growth responses to external stimuli. The direction of movement is not determined by the direction of the stimulus, as are tropisms. Instead, nastic movements are caused by changes in turgor pressure (pressure exerted by water inside plant cells against the cell wall) in specific cells, which result in the folding or unfolding of plant parts. The main types of nastic movements include nyctinasty, thigmonasty, seismonasty, thigmonasty, and hydronasty. Nyctinasty involves the rhythmic opening and closing of flowers or leaves in response to changes in light and darkness. Thigmonasty involves the non-directional movement of plant parts in response to touch or physical contact. Seismonasty involves the movement of plant parts in response to mechanical disturbance or vibration, often as a defense mechanism against herbivores or environmental stress. Thermonasty involves the movement of plant parts in response to changes in temperature, and hydronasty involves the movement of plant parts in response to changes in water or humidity levels.

The differences between tropisms and nastic movements lie in their directional response to external stimuli. Tropisms involve directional growth responses towards or away from a stimulus, while nastic movements are non-directional, reflexive responses to environmental stimuli. For example, phototropism involves a directional response to light, where plants bend towards or away from the light source. In contrast, nyctinasty involves a non-directional response to changes in light and darkness, where flowers or leaves open and close rhythmically. Thigmotropism is a directional response to physical touch or contact, whereas thigmonasty involves a non-directional movement of plant parts in response to touch or physical contact.

Moreover, tropisms typically involve the differential growth rates of cells on opposite sides of the stem or root, which cause bending towards or away from the stimulus. In contrast, nastic movements are caused by changes in turgor pressure in specific cells, resulting in the folding or unfolding of plant parts.

Knowing the differences between tropisms and nastic movements is crucial in studying plant growth and development, as they affect the overall morphology and physiology of a plant from environmental factors.

Plant Intelligence

Plants lack a centralized nervous system and brain, yet they display complex behaviors and responses to their environment. These include the ability to communicate with each other through chemical signals, and even to recognize and respond to their kin. The appear intelligent, just not in the discursive manner expected by reductionist science.

There is evidence that plants communicate through ultraviolet and infrared light signals, as well as through electrical and electrostatic signals. Some studies have shown that certain plant pigments absorb and emit light in the ultraviolet and infrared ranges, which may serve as a means of communication between plants. Plants generate electrical signals in response to stimuli such as touch, which travel through the plant and potentially be used to communicate with other nearby plants. There is evidence to suggest that plants generate and respond to electrostatic fields, although the precise internal sources of these processes are yet not known.

While tropisms may indicate a form of plant intelligence, they are seen in science as only innate responses to stimuli, as they do not involve decision-making or learning. Nastic movements, such as thigmonasty in Venus Flytraps, are natural growth movements and not currently considered signs of intelligence.

There is some evidence to suggest that plants can learn and that certain traits may be transferred epigenetically. One study (doi:10.1007/s00442-013-2873-7) published in the journal Science in 2014 showed that Arabidopsis plants learned to associate a light stimulus with a mild electric shock, and that this learning could be passed down to their offspring through epigenesis. The researchers found that the learned behavior persisted for at least two generations, and that it was associated with changes in DNA methylation patterns in the plant's genome.

The study of plant intelligence continues to evolve and offers new insights into the complexity and adaptability of the plant kingdom. One may consider that all these complex and diverse aspects of plant growth and interrelationship, via their various methods, are expressions of an innate intelligence, each type expressing itself into the biosphere.

The Plant Family in Space and Time

“In nature we never see anything isolated, but everything in connection with something else which is before it, beside it, under it and over it.” — Goethe

Goethe viewed the entire vegetative surface of Earth as a manifestation of the archetypal urpflanze, which he saw as the idealized, spiritual form of all plant life. He saw the urpflanze as the fundamental pattern or blueprint that underlies the diversity of plant forms we see in Nature. According to Goethe, the urpflanze is the purest expression of the plant archetype, and all individual plant types are variations or modifications of this archetype. In this way we can envision the entire plant kingdom as a unified whole, with each individual plant reflecting the essence of the urpflanze in its own unique way.

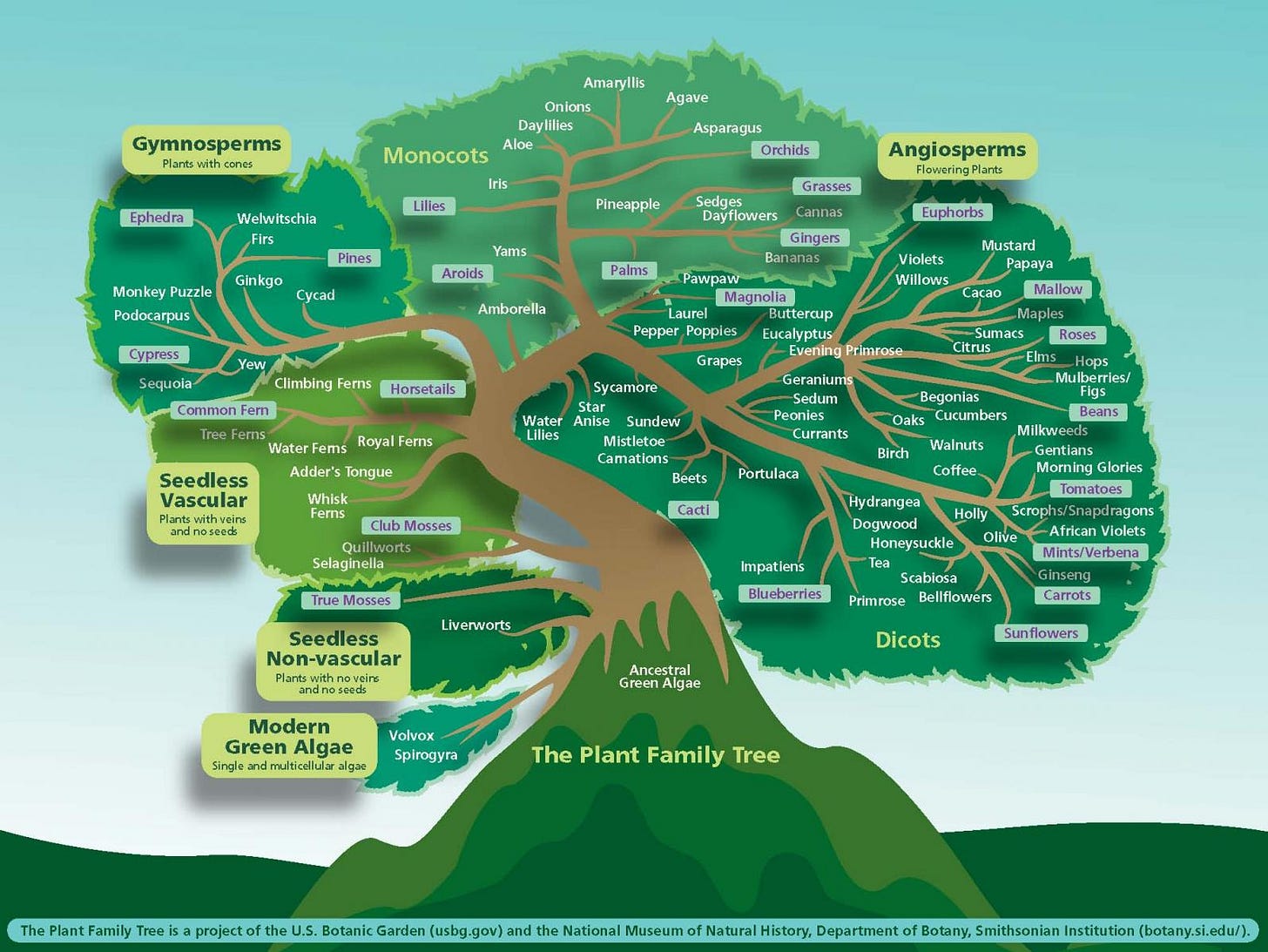

The diversity of plant types that have evolved over geological time can be seen as a magnificent expression of Goethe's theory of the urpflanze. The earliest plants lacked roots, leaves, and complex vascular systems, but as time progressed, more sophisticated structures developed, leading to more efficient nutrient uptake and photosynthesis. The emergence of seed-bearing and flowering plants during the Mesozoic Era facilitated the diversification of plant life and led to a wide variety of reproductive strategies. The first flowers appeared during the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous period, and co-evolved with pollinators such as insects and birds to become a crucial component of terrestrial ecosystems.

The amazingly “coincidental” rise of flowering plants and specialized pollinating insects, such as bees, butterflies, and moths, led to an explosion of diversification in both groups, providing efficient pollination services and contributing to the ecological success of these plants.

Through this process, the urpflanze has unfolded its potential into an infinite variety of forms, each expressing its unique character and purpose. This diversity of plant types can be viewed as the ultimate manifestation of the metamorphosis of plants, demonstrating the power of the urpflanze to adapt and evolve over time, and a testament to the creative potential of nature and the wonder and complexity of life on Earth.

So in envisioning the whole of a plant in our imagination, relating it through the Goethean method to the full vegetative surface of Earth in the present and past, we gain an incredibly deep insight into the metamorphosis of the biosphere over geological time frames, at least at this point from the faunal perspective. Every individual plant is connected throughout this cognitive structure.

Cosmological Botany

If just an idea, then does urpflanze have a residence in matter or in spirit? Is there a realm where the Idea operates, bringing forth the form and functions of the plant world?

Plants are integral organs of the environment, rooted into Earth, reaching for the heavens. People have always noticed the effects of the movements and patterns in the heavens, on earthly life, and especially on plants.

Obviously the Sun, our largest and most dominant cosmic neighbor, is directly related to plant growth. It’s daily cycle regulates most life on Earth, and some plants and flowers are heliotropic, as we’ve discussed earlier.

Our Moon influences agriculture, with many farmers and gardeners following lunar cycles to guide their planting and harvesting. The various phases affecting plant growth and development. The waxing phase, when the moon is increasing in size, is the best time for planting above-ground crops, while the waning phase, when the moon is decreasing in size, is the ideal time for planting below-ground crops. The moon's gravitational pull is thought to affect water movement in the soil, impacting seed germination and plant growth. It has been suggested that the Moon’s effect on tides in the ocean can influence the moisture content of the soil and thereby the growth of plants.

Yet, is there more to the influence of the cosmos on plant form and growth?

We see that plants are always expanding into their environment, reaching outwards as if to touch something intangible, with the final flowers, whose beauty gazes to the heavens. Earthly life is immersed in force fields, the rhythmically fluctuating electric and magnetic fields of earth, which are constantly influenced by Earth's cosmic environment. In this cosmic environment we may find indications of the ideal formative principles of plants.

Planetary Influences Upon Plants - A Cosmological Botany, by Ernst Michael Kranich, provides astonishing insights related to the Goethean approach of seeking the realm of the urpflanze. This approach theorizes that the form of the flowering plant is influenced by the surrounding planetary worlds. To summarize: The seed is a prerequisite for a self-contained plant form and is associated with Saturn. Moon's isolation of the effects of the Sun and Mercury influences seed development. Fruit development is linked to the image of Jupiter oriented towards the Zodiac, while the ovary is associated with the isolation of Mercury's effect by the Moon. Stamens and pollination are linked to the role of Mars, while Venus is linked to the perianth moving out into the periphery of the Sun's sphere. The movement of Mercury closely tied to the Sun is related to the leaves, while the Sun and its movement are linked to the center shoot. Finally, the Moon is associated with the root. These designations provide some insights into the cosmological botanical ideations derived from the Goethean approach, which are too lengthy for this short article. The reader is directed to obtain a copy of this amazing book for further investigation of the concept.

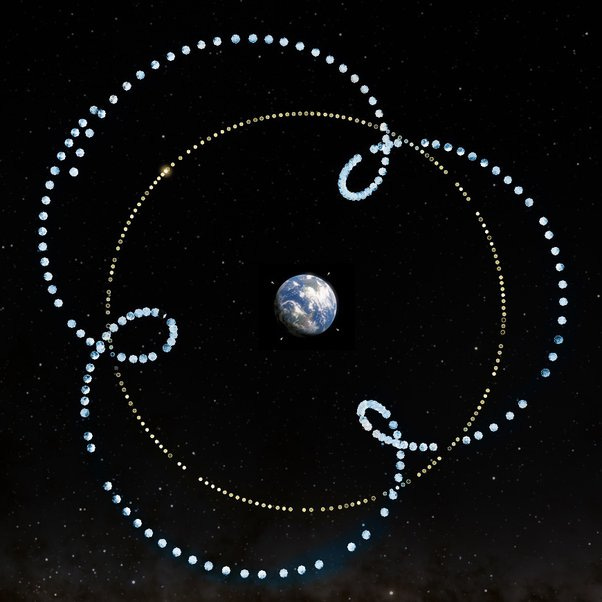

We do find in the heavens distinct morphological patterns in cosmic relationships as seen from Earth, the so-called “apparent motions”, but obviously the experiential ones directly influencing Earth life. This is the Tychonic universe, after Tycho Brahe, some see as geocentric, but more properly anthropocentric, as it involves the influences of the relationships of cosmic bodies on Earthly life, moreso that attempting to determine the absolute position of Earth (which will be discussed in future articles).

“The connection between the movement of the sun and the development of the center shoot becomes apparent only when the sun is seen in relation to earth. For life on earth, happenings in the universe are to be taken into consideration only to the extent that they are mirrored on earth , i.e., how they appear when seen from earth. Therefore one must proceed strictly from the phenomena. For this reason the heliocentric view of the world, for our purposes, is not applicable. It is not a phenomenon; it is instead constructed from phenomena, with the support of certain assumptions. Seen from earth, nothing points to the sun as the center of the planetary system and to elliptic orbits of planets. For the earthly plant kingdom, the universe as seen from earth is of importance, not the thought-concept man has of it. Insofar as there are connections between the plant kingdom and the motions in the planetary system, they can be decoded through a geocentric approach alone and not by using the heliocentric system.”

— E.M. Kranich, in Planetary Influences Upon Plants

In the Mercury-Sun synodic cycle we find the archetypal pattern of the monocotyledons, with its fundamental form of three petals and three sepals in the perianth.

In the Venus-Sun synodic cycle we find the archetypal pattern of the dicotyledons, with its fundamental form of five petals.

Naturally there are variations in the forms of monocots and dicots, but the fundamental archetypal form is represented in the majority of types.

We shan’t delve too deeply into cosmological botany in this article, that’s a lengthy study in itself. Herein is provided a general introduction to the idea, to present the concept for further research and study, and integration into meditations on cognizing the full extent of the plant world and its influences. Ideas one may follow in seeking the urpflanze in the ideal realm of archetypes. From seed to seed in Goethe’s process, and through the biosphere to the heavens with his method.

Considerations

What I have attempted through this article is to provide a greater idea, through my experiences in seeking cognition of the urpflanze, which one may follow in their own time and relationship with manifestation. I have presented a wide range of aspects of the physical plant realm which I have directly experienced in consciousness along my sojourn into awareness of the natural world of which I am an element.

Expressing archetypal visions is not readily amenable to descriptive wordings, it is more able to be expressed through scientific and spiritual aspects as I have presented herein, taken as an overall metaphor to resonate in consciousness. Or perhaps seen through symbolic arts, but even such as that requires description or initiation of process, and cannot fully express the cognitive organ of the archetype as it exists in higher states of consciousness. One must find their way themselves, just as one may not grow muscles by merely reading an exercise book.

Naturally this is still all a work in progress for me, which I am chronicling here as a personal process of working through ideas that arise in my consciousness, sharing the output in the hopes some find it useful.

So in summary, we may seek to cognize now, as a meditative imaginatory exercise, the whole of the plant as foundation to knowing the urpflanze;

We consider the individual plant type’s flow in time, from seed to seed as a wholeness of being beyond the discursive moment of waking observation,

Its phases of growth and tendencies envisioned as a whole in our imagination,

Its etheric and astral aspects,

Its symbiotic biospheric interrelationships with other flora, fauna and interconnections with the microbiome, as a member of the biospheric floral family which constitutes the expression of the urpflanze in present time,

Its environmental tropisms and nastic movements,

Its innate intelligence in adaptation and signaling through chemical, electrical and IR and UV light signaling,

Its presence as a stage of plant metamorphosis through time, looking back into the distant past as earlier stages of the biospheric floral family, to see that as a deeper expression of the urpflanze,

Its cosmic morphological “signature” relationships leading to the cosmic source of the urpflanze, which provides foundation to cognizing the spiritual nature of the cosmos, especially by becoming aware of the anthropocentric reality surrounding our living planet, a great gift to our consciousness when attained.

Dandelions & the Sun

Now, back to the dandelion, an incredible healing herb, which is a remarkable representation of the forces of light and the Sun. It follows a beautiful and radiant flowering process, wherein the flower heads contain numerous flowers that bloom in circles from the edge towards the middle.

Being a Compositae, the single petals in each apparent flower are individual flowers. These flowers are adorned with radiant yellow or reddish-orange rays that intensify over several days, representing the interior part of the flower turning towards the light. This aspect creates an intimate connection of the plant with the Sun.

When the dandelions are in full bloom on a meadow or mountain pasture, it is a sight to behold as the Sun and plant life unite into one entity. The dandelion heads open in the morning and close in the evening and during rain, reflecting the sunrise and sunset a thousandfold in a meadow.

“Nature is the living, visible garment of God.”

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe